The anatomy of stress and how to bio-hack it

By Janelle Kwong | 23 March 2020

We all experience stress differently

We may notice stress as an emotion we feel, as a sense of overwhelm when too many curve-balls come our way. Stress may be experienced as a series of thoughts; worries that circle in our heads and distract us from our work, sleep or other tasks we need to perform from day to day. At other times, we may even recognise the way stress manifests in our bodies, perhaps as a headache, tightness in our shoulders or some other physical pain or constriction.

The way we experience and respond to stress varies from one person and one situation to the next. This stimulus-response process works in fascinating ways. The more repetitive the stressful episodes are in our lives, the more hard-wired we can become in the way we deal with them.

But what if our default instincts can be ‘re-wired’ and our stressful energy repurposed? For Doaa Alsayed, avid reader, researcher, nutritionist and inaugural guest speaker for GT Insights, it all begins with awareness. By knowing our situational, emotional or psychological triggers in a moment of stress and by understanding the physiological impact this has, we can use simple behavioural changes to help hack our stress responses out of their usual patterns.

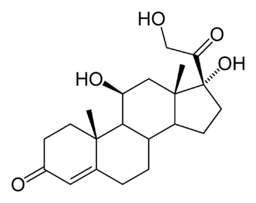

Upper image: Cortisol-2D-skeletal Benjah-bmm27 on Wikimedia Commons

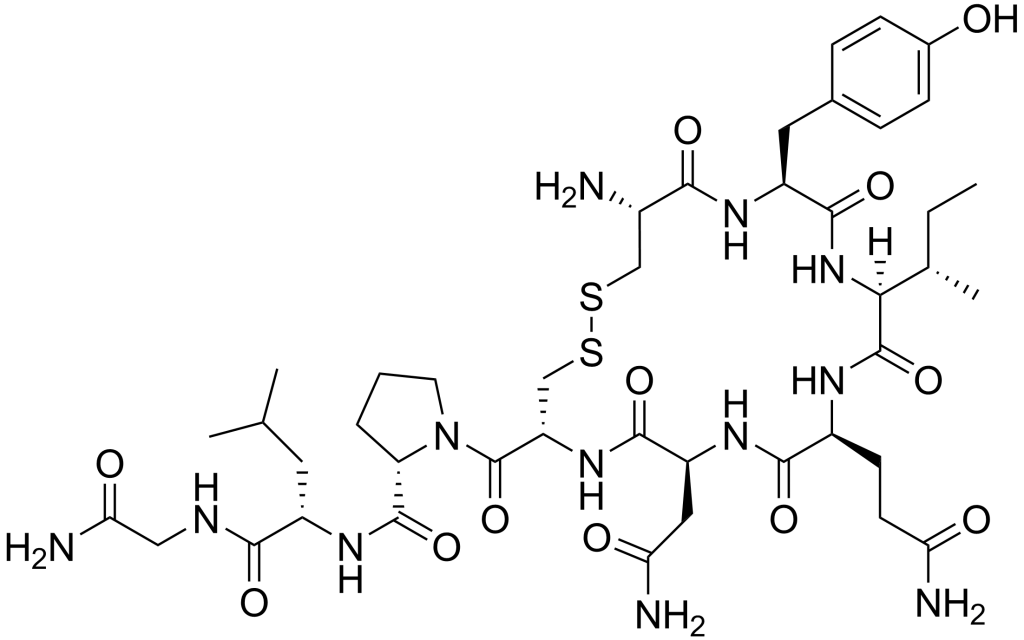

Lower image: Oxytocin by Edgar181 on Wikimedia Commons

Good, bad or both?

In some instances, an acute episode of stress may be just the thing we need. It can give us an extra burst of energy to help protect us from physical harm, or simply give us the confidence boost we need before a major presentation.

More often than not, however, stress can go unmanaged, becoming a constant part of our daily lives. When this happens, even when the triggers are only mild, we lose the benefits that the body’s stress responses can bring. Our bodies remain in a chronic state of hyper-vigilance and we find ourselves struggling to ‘simply’ relax. We may eventually find ourselves normalising our experiences of stress, perhaps to numb ourselves of its consequences, even to the point of damaging our mental and physical wellbeing.

Fortunately, we can also make positive choices when it comes to dealing with our daily stressors. By default, we may react to stress with stress (be this in an elevated, controlled or suppressed form), but our default option is not the only one available to us. It may seem like a tall order but, when it comes to choosing our emotional and behavioural responses, we do hold some agency, some of the time. With awareness and training, perhaps we can even build a new default of our own choosing.

But wait, awareness of what exactly?

Our guest speaker, Doaa Alsayed, breaks this down for us, beginning with an understanding of our body’s acute stress response, commonly known as the fight or flight reaction. When faced with a threatening situation, whether physical or psychological, a component of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) kicks into action. The ANS operates without our conscious direction, looking after life-sustaining processes like breathing and heart function without us needing to think about it.

Fight or flight

When faced with an imminent threat, our sympathetic nervous system (the component of the ANS that manages the stress response) prepares the body to tackle the problem head on or escape to safety. As a result, we may notice changes in our body as our heart rate speeds up, our breathing quickens, adrenaline pumps through our bloodstream, and other physiological processes are activated.

Freeze

In other instances, we may enter a ‘freeze’ response. When we assess a situation to be too dangerous to confront and too powerful to flee, our best defence may be to make ourselves ‘disappear’. Our body releases endorphins and other chemicals that help buffer the pain we are exposed to. We neither fight nor flee, but we do our best to create mechanisms that facilitate numbness to or dissociation from a situation we deem too unbearable to take in.

Stress-dependence

Our fight/flight/freeze responses are easy to identify in situations of extreme physical danger, but can also translate to everyday stressors. We are more prepared to burn the midnight oil one night before a major deadline (the ‘fight’ response), but won’t find ourselves with the same energy for this when the due date is still far away. When we find a task too challenging, we may be more inclined to delay (or ‘flee’ from) it. Alternatively, we may ignore our stressors altogether, constantly telling ourselves that things are okay and not worth worrying about (numbing).

These responses are helpful temporarily, but when we constantly draw on our acute stress responses to get from one moment of our day to the next, we flood our bodies with too much cortisol and other stress hormones, leaving us with an elevated heart rate, shallow breathing, inhibited digestive processes, and excess ‘nervous energy’.

Keeping our bodies in this heightened state affects our concentration, mood and sleep patterns. It may also interfere with organ function, making us more vulnerable to weight gain, high blood pressure, a weakened immune system, diabetes and other health problems over time.

KonMari your chronic stress

It may sound trite, but once we become aware that our bodies are in a reactionary fight/flight/freeze state, it’s a lot easier to de-escalate with gratitude than with force. In the words of Marie Kondo, “let go with gratitude”.

Take pause, breathe deeply two or three times, acknowledge your feeling of stress and thank your stress responses for keeping you safe. Then, like you would for a trusty pair of socks that won’t survive another trek, farewell your stress and make KonMari proud.

See it, thank it, hack it

Much like the stress response, our relaxation response can be triggered by environmental, psychological and behavioural stimuli and is also a part of our ANS. This part of the ANS, known as the parasympathetic nervous system, works to restore our body to its ‘rest and digest’ functions. It metabolises excess adrenaline, slows down our heart rate, relaxes our muscles and releases anti-stress hormones that help us feel calmer and happier.

So, the next time you notice your stress levels rising or to simply keep all components of the ANS in healthy symbiosis, try incorporating some of these hacks into your life to help bring about a more chilled-out, relaxed you

Breathe

Breathing is one of the most accessible ways for us to bio-hack the usual stimulus-response process we are drawn into when under stress. Long and slow breaths activate the vagus nerve, a collection of motor and sensory fibres that connect the brain, heart, lungs and gut (plus other vital organs). The vagus nerve is a key access point to our parasympathetic nervous system, which is responsible for our relaxation response.

Eat healthy

If you’re going to binge anyway, find healthy substitutes and make them easier to access. Keep the chocolate out of sight and the ice cream at the supermarket. Perhaps prepare some raw protein balls and engage your tactile senses in the process. Tactile stimuli draw attention to physical sensations, which can help deactivate the sympathetic nervous system (which triggers our fight of flight response) and cultivate a greater sense of calm. Eating also activates touch receptors in the mouth and, when food reaches the gut, triggers the release of a hormone to activate the vagus nerve.

Kiss

Kissing, or gently tapping your lips with your fingertips, triggers the release of oxytocin, the ‘love hormone’. This is the hormone that gives us the ‘warm and fuzzies’ we feel when we see or experience acts of care and tenderness. It decreases blood pressure and cortisol levels and is associated with the ‘tend-and-befriend’ behaviours.

Get into nature

Take a hike, literally. Surround yourself with trees, flowers and fresh air. Soak in the sunshine or watch the world go by from the dappled shade of your favourite elm tree and allow the calm to wash over you. Being in nature triggers the relaxation response and gives the body an opportunity to rest, breathe and heal.

Laugh

Support your favourite comedian, revive your most embarrassing dad jokes and celebrate more silliness. Laughter relaxes muscle tension in the face, neck and diaphragm, which helps to stimulate the vagus nerve. Laughter is also a natural immune booster and, as the saying goes, it's the best medicine.

Exercise

When we release stress through exercise, we repurpose the adrenaline in our body and also release endorphins that boost our mood. After a workout, the body automatically switches to rest and relaxation mode, actively slowing down the heart rate and releasing tension from the muscles.

Yoga

Yoga combines the benefits of exercise, breath and meditation, helping to strengthen vagal activity. A stronger vagus response helps our bodies to enter relaxation mode with less effort after a stressful situation and in everyday life. By including chanting in our yoga practice we will also be producing vibrations in the neck, another point of stimulation for the vagus nerve.

Sing and dance

Singing an upbeat song activates the vagus nerve and lifts our spirits. Dancing, like exercise, can release endorphins into the bloodstream and get us out of our heads and into our bodies. Better still, learn to sing a song in a non-native language. This requires us to reduce the dominance of sympathetic nervous system activity by stimulating a different part of the brain.

Snuggle with your pets

Pets have an incredible way of grounding us, drawing us into the moment and (for some) demanding our undivided attention. This can conveniently lower sympathetic nervous system activity, reduce cortisol levels and trigger the release of ‘happy chemicals’.

Give it time

Just as the incremental stressors of daily life can build up without us noticing, the difference we feel from the small positive changes we introduce into our lives may seem negligible to begin with. However, for those of us spending too much time in a reactive stress mode, the more intentionally and more frequently we switch on our parasympathetic nervous system, the healthier, calmer, stronger and more relaxed we become.

Image attributions

Photos sourced from Unsplash

References:

LeBouef T, Whited L. (2019) Physiology, Autonomic Nervous System. [Updated 2019 Feb 12]. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 January [online]. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538516/ [Accessed 23 March, 2020].

Porges, S.W. (1992) Vagal tone: A physiologic marker of stress vulnerability. Pediatrics 1992; 90:498–504 [online]. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ [Accessed 23 March, 2020].

Society for Endocrinology (n.d.) You and your hormones: An education resource from the Society of Endocrinology [online]. Available at https://www.yourhormones.info/hormones/ [Accessed 23 March 2020]